How to Be Afraid

Skills to tolerate the distress of resisting, even existing in these times

There's something uniquely American about our relationship with speaking truth to power. We mythologize it while often shunning and punishing those who do it. We name elementary schools after historic dissenters while creating increasingly sophisticated systems to silence contemporary ones.

This week, a journalist asked me about a rumor that my lawsuit was backed by George Soros as part of a broader, coordinated campaign against Meta. A campaign that includes Sarah Wynn-Williams, Frances Haugen, because the credibility of our claims and their timing with federal inquiry is too well timed.

I laughed.

It's easier to believe we're puppets in some grand conspiracy than to accept that we're individuals who reached similar conclusions from similar experiences. Like avalanches that fall long after the last snowflake has hit, systems of silence hold until they don't.

Conspiracy theories like this also reflect something deep and unspoken about our society: we don’t know how to be afraid. We fear being shamed, wrong, alone, or exiled. The Soros rumor externalizes all that fear, it provides an explanation.

The truth is there’s no George Soros behind me, or anyone bank rolling me. The truth is that I am in fact staring down potential financial ruin.

I confronted a lot of fears, it was like putting my eye up to a dark barrel of total uncertainty over and over with lots of support until I could look long enough to parse the fear.

I was scared about financial consequences, yes, but I was also afraid about the discrediting campaigns I’d been warned about. With my skills and capacity so adrift in recovery, reputation and credibility were my sail.

As such, when I researched other tech whistleblowers while preparing to file, I asked AI if there was any risk of referencing them during press as I planned to (and as I did).

Truth tellers like Sophie Zhang, Ifeoma Ozoma, Aerica Shimizu Banks, Frances Haugen, and Ellen Pao.

AI’s response was something like, “Don’t talk about any of them. Women who stand up to tech companies never walk away with their credibility intact, due to discrediting efforts and career damage from speaking out.”

The recognition hit immediately that I was signing up to be part of the group of women forever discredited.

Moving forward required accepting that fear and staying with it.

“We are all afraid,” Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska said last week at a conference in Anchorage, “…I’m oftentimes very anxious myself about using my voice, because retaliation is real.”

As Senator Murkowski modeled, it’s not about waiting for an absence of fear. Courage is about being with ourselves and with fear together

The Paradox of Truth Telling

Generally, people seem to appreciate and applaud those who use their personal capital to speak truth to power, yet many are afraid to do the same. Others wish for a world where people cut the bullshit, then immediately call bullshit on those who do.

We reject what seems impossible, and speaking truth to power can seem really impossible, but it's possible.

We see that as New York Attorney General Letitia James stands against federal overreach, as Governor Janet Mills of Maine promises court action against anti-transgender threats, saying to Trump, “see you in court!”

Professors and journalists document academic censorship, and as thousands of unnamed others place their bodies and careers between their communities and harm. What connects them isn't exceptional bravery. My take? It's their ability to feel afraid and act anyway.

Like Harvard President Alan Garber declaring "No government should dictate what private universities can teach" while facing a $2.2 billion funding freeze, or journalist Karen Attiah launching her own course after Columbia dissolved her department, saying "They can try to cancel us all they want. But this is the community we're building anyway."

These aren't people who've conquered fear, but those who've learned to carry it like an uncomfortable bag; necessary, heavy, but ultimately portable. It’s coming along for the ride.

It’s not about working up the courage to finally take some big future step, it’s the quiet decision to be uncomfortable on purpose, for a purpose.

Some of this I learned 10 years ago, standing on tennis balls in a birth prep class.

The rest of it, I learned when I was in trauma treatment.

DBT-PE (Dialectical Behavior Therapy Prolonged Exposure) is a treatment designed for suicidal people with PTSD. Developed by Dr. Melanie Harned, DBT-PE integrates the life-saving structure and skills of full fidelity DBT with the gold-standard trauma therapy of PE.

As one component of the treatment, the client vividly reimagines traumatic memories in the present tense, usually aloud during sessions, over and over, to:

Reduce avoidance

Weaken fear structures

Allow emotional processing and inhibitory learning

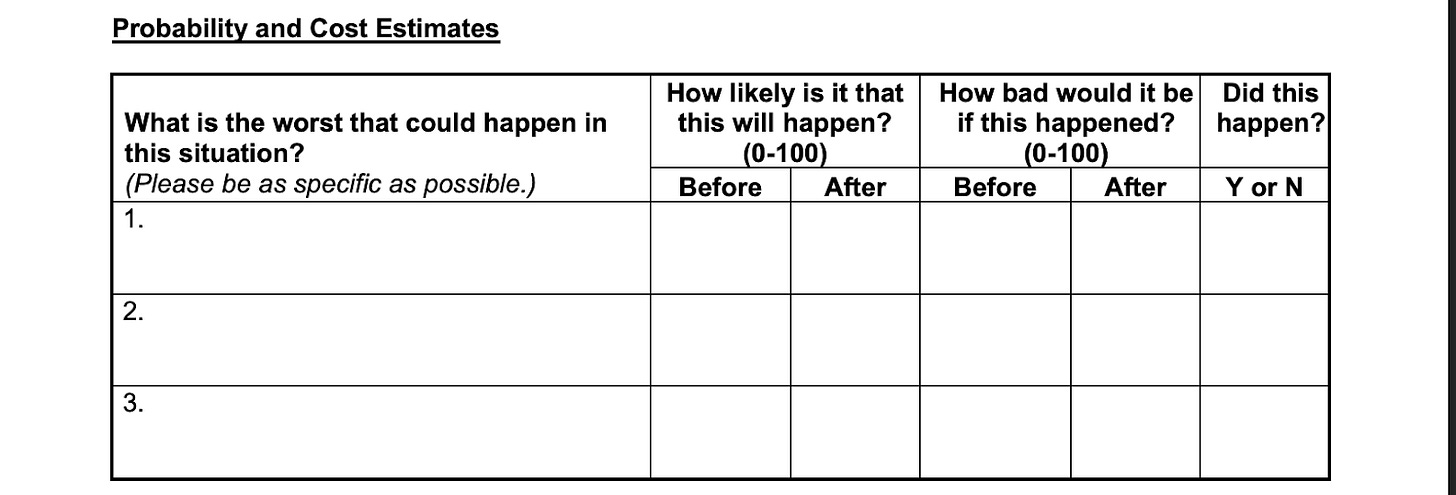

It can be easier to avoid trauma than to confront it, but DBT-PE requires confrontation. To prepare for and recover from exposures, we used something called an Exposure Recording Form. Questions from the "Probability and Cost Estimates” section comes up for me every single time I steady myself for values-aligned behavior despite fear or distress.

For me, it’s useful for both little and big things; from disappointing my kids with tonight’s meal choice to making the decision to stand up to Meta.

And this DBT framework offers questions we can ask ourselves collectively, as we live through one prolonged trauma experience together.

When we resist power structures that threaten to smother us– whether downloading the 5 Calls App and committing 5 minutes a night to calling Congress, like Dr. Colleen Reichmann suggests, or saying “I need a minute” when circumstances urge you to push through, like Paul Shattack included in 80 Tiny Moves for Everyday Resistance–we can ask ourselves:

What is the worst that could happen in this situation?

How likely is it that this will happen?

In many cases, we fear some form of distress, like shame, sadness, humiliation, or fear. In others, we fear a financial catastrophe, or the loss of a relationship. Sometimes the fear is homelessness, illness, death. Sometimes it’s rejection from a group you value. Making a plan for what you will do if that feared thing comes to be is a very effective way to take the air out of the balloon pressing against you.

If it does happen, how will I respond?

How will I stay committed as distress increases?

What’s my backup plan?

In the case of reliving painful memories, these questions helped me build a plan that balanced safety with courage. If distress spiked during or after a memory resurfaced in treatment, I could take a break, grounding myself with sensory input, moving my body, or naming objects in the room. I could turn to distress tolerance skills like paced breathing and putting my face in an ice bath. To stay committed to treatment as the intensity rose, I kept visual reminders of my goals and deescalation plans, and I shared my crisis plan with a few trusted people.

The point isn’t to power through, it's to prepare with enough care and structure that I can keep choosing my values, even when it’s hard.

Systems that oppress us operate in plain sight, protected by our collective agreement to look away, to call them normal, and to accept them as inevitable. This is the harder truth, and facing it requires more courage than it takes to conjure conspiracy theories.

Instead of just imagining the worst, like an ICE officer showing up at a community event, we can decide exactly how we want to respond, and then start clearing the barriers that might get in the way. We figure out what calm, principled behavior would look like for us, what support we’d need, and how we’d stay steady if distressing emotions surged.

This is how I filed a lawsuit, this is why doing so required so much support, which is also why many can’t, which is also why those who can must — but that’s another newsletter.

This approach works in smaller moments too, like speaking up the next time someone says something harmful in a meeting. Rather than freezing then stewing about it afterward, we can prepare for what we’d want to say, practice it, and plan how we’ll ground ourselves if it’s uncomfortable. Plan for how we’ll manage our worst fears.

Making a plan shifts us from helplessness to readiness. It helps us stop circling the obstacles and start making room for our values to land.

Resistance is the process of aligning our behavior to our own values instead of the values of those in power, even if it’s uncomfortable, even at a cost. Even if it’s terrifying.

Which means managing to do hard things isn’t about having a George Soros in your back pocket, it isn’t about possessing innate traits of fearlessness, it isn’t about something only available to the elite, it’s about skills.

This is the opportunity: to be with our fear long enough to recognize the catastrophe of inaction is likely far worse than the catastrophe of action.

This is how we come into alignment with our values, no matter how fast the sky is falling. This is also the way the resistance builds, stretches, towers, and becomes a roof over our heads.

This is about cultivating new skills to face what’s ahead, no matter the uncertainty, no matter the threat.

And that’s also uniquely American.

For those interested in learning more about DBT, you can find a clinician here, or jump into some great free resources like Gajan Retnasaba’s free course and skills overview and Rutgers University’s DBT RU.

Proud of the work you’re doing. It takes courage. Thank you!

Your courage is inspiring ❤️I personally also admire protesters like Ibithal who spoke up about the use of AI at the Microsoft 50th anniversary. The resistance from these women takes guts