The College Success Foundation (CSF) has helped thousands of Washington State and Washington DC students—especially low-income, first-gen, and foster youth—access and succeed in college. I joined the CSF board last year because I believe in its mission: every student deserves a pathway to higher education, not just the ones who can afford it.

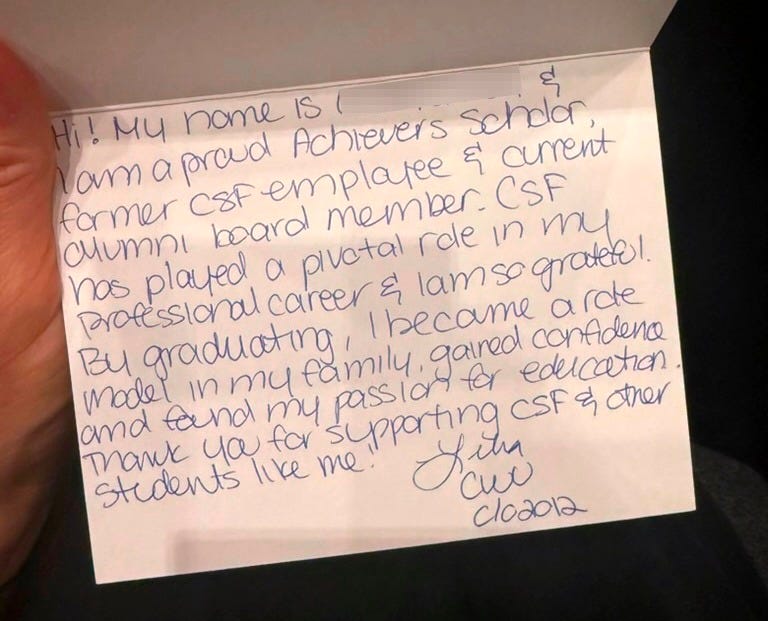

A couple of weeks ago, an emergency board meeting was called. It was a sobering, stark contrast to our 25th Anniversary Gala, where we celebrated a quarter century of impact with a packed ballroom, hundreds of handwritten thank you notes from CSF students, and speakers like former Washington Governor Gary Locke, Costco Co-Founder Jim Sinegal, and Washington State Senator and CSF graduate, Yasmin Trudeau.

A few weeks later, we’re on a Teams call, shocked.

CSF, like so many nonprofits, is facing catastrophic funding cuts. As Dahlia Bazzaz reports in the Seattle Times, CSF has lost more than $12 million in state funding and is being forced to “shrink its staff from 150 to 54, gutting its ability to counsel students from their middle school years up until college graduation.”

The magnitude of this loss is hard to overstate. CSF isn’t just a scholarship provider, but a hands-on support system for low-income and first-gen students from middle school through college. Slashing our staff by nearly two-thirds means 20,000 students will lose trusted adults who walk alongside them through FAFSA, applications, college transitions, and crises.

“Dropout rates will increase and declines in FAFSA completion and college enrollment are imminent. The ripple effects could be long-lasting and severe, threatening the well-being of families, the future of our children, and the strength of Washington’s workforce for years to come.”

– James Dorsey, CEO, CSF

Decreasing access to education is not what our communities need right now. Protecting education is protecting our community’s ability to think critically.

And it’s not just education in crisis. It’s not just CSF.

CSF's crisis reflects a broader pattern devastating nonprofits nationwide. Nonprofits across sectors are being gutted while demand for their services soars.

In March 2025, the Trump Administration announced it was clawing back ~$11–12 billion in pandemic‐related public health grants. Reuters reports HHS canceled “around $12 billion” in CDC and SAMHSA grants to state and local health departments. Senator Patty Murray noted over $160 million cut from Washington state alone. In April 2025, the Nevada Attorney General, Aaron Ford, joined 23 states in suing HHS over its abrupt termination of $12 billion in public health grants.

Government funding is stretching and vanishing as need increases. They call it a “matter of margins” while those on the margins drift further away.

The Consequences of Defunding Nonprofits

Cutting funding for nonprofits often eliminates programs that save taxpayers money in the long term. A wealth of research shows that every dollar invested in preventive and supportive services yields multiple dollars in economic returns.

When nonprofits shutter, the consequences ripple far beyond a single organization. These closures often begin a domino effect that hits the most vulnerable hardest. Many nonprofit workers, already earning modest wages, suddenly find themselves unemployed, without a safety net, and in need of the services—housing aid, mental health support, food assistance, youth programming—that were cut with their jobs.

Early Childhood Education: Investments in high-quality early learning can return as much as $7 for every $1 spent, thanks to improved health outcomes, higher lifetime earnings, and reduced need for social support.

Afterschool & Summer Programs: Rigorous state-level studies find at least $3 to $12 in savings to taxpayers for every $1 invested in afterschool programs. A recent analysis in Pennsylvania showed a $6.69 return per $1 by reducing high school dropouts, teen pregnancy, substance abuse, and crime. In other words, funding afterschool activities now means lower costs for remedial education, law enforcement, and public assistance later.

Youth Mentoring and Graduation: One analysis calculated that every $1 invested in a youth program can benefit society by about $10.51. This 10-to-1 payoff doesn’t even count the additional savings if that student avoids incarceration or chronic unemployment. Keeping a teenager on track through graduation is among the most cost-effective public investments we can make.

When we pull those dollars back, we don't save. We shift the cost somewhere else. And it usually lands on ERs, public schools, police departments, and families already stretched thin. One study found that stable housing for chronically homeless individuals can save cities up to $29,000 per person per year in reduced emergency costs.

In Washington state, proposed 2025–27 budgets would eliminate nearly all public school grants that support at-risk youth. For example, Treehouse – a Seattle nonprofit serving students in foster care – relies on about 65% of its program funding from state education grants. With those grants slated for cuts, its CEO warns in an interview with Everett Herald that it will have to “cut back its work” serving vulnerable youth. Similarly, the Ninth Grade Success program (supporting high-needs 9th graders) would lose a $3 million grant, jeopardizing gains in graduation rates.

Nonprofits in affordable housing and community development are facing cuts to federal funding. A national Shelterforce April 2025 report details how Trump‐era HUD cuts slashed technical‐assistance grants, hurting hundreds of nonprofits across the country.

Public and community health providers have also been hit. In Texas and elsewhere, federal cuts to pandemic‐era public health funding have forced local departments to halt work. For instance, after HHS canceled COVID‑relief grants in March 2025, the Lubbock Health Department abruptly stopped a measles outbreak vaccination drive funded by CDC grants. Similarly, seven community health centers in Boston warn that proposed Medicaid cuts under the Trump administration pose a “serious threat” to patient care.

Nonprofit food and nutrition programs are affected, too. Sharing the Harvest reported that a March 2025 USDA funding cut hit their Central Texas Food Bank hard, saying that critical donations, especially meat and other proteins have dwindled due to these cuts “and an inexplicable drop in contributed food…” A Rhode Island nonprofit, Farm Fresh RI, announced $3 million in USDA cuts in February 2025, jeopardizing over 100 local farms.

Multiple data sources and reports from 2023–2025, including national surveys (Urban Institute, MassINC/TBF, United Way), business journals, and expert commentary (NCN, NPQ, news outlets), document this nationwide trend.

Private philanthropy isn't filling gaps fast enough, despite unprecedented wealth sitting in foundations and donor-advised funds.

Philanthropists Katie and Brian Boland of Delta Fund wrote recently about the urgency for a spending revolution. “We love to celebrate the power of financial compounding, marveling at how money grows exponentially over time. Yet, we overlook something equally profound: the compounding effect of human impact,” they preach (and to that I say, preach!). They urge investors to “adopt spend-down strategies, prioritizing immediate, significant investments in people, communities, and systemic change.”

The “compounding effect” of social impact investments return for generations. When we underfund these services, we’re not “saving” money at all. We’re forfeiting huge returns.

The impact of CSF’s defunding will be more students falling straight past the shadows of safety-nets. Compounded, each high school dropout is estimated to cost the economy about $272,000 over a lifetime in lost earnings, lower tax revenue, and higher public assistance spending. One analysis found that each cohort of dropouts nationwide costs over $200 billion in lost economic output and additional social costs. By contrast, the cost to help a student graduate (through mentoring, tutoring, or college prep and scholarship programs) is a tiny fraction of that.

There is no alarm bell for the quiet end of opportunity, no televised moment when a teenager’s future is made more grim. But the glue holding our communities together is melting, now.

We Can Slow the Melt

Support Prevention and Core Services: It can be tempting for donors to favor “shiny” new initiatives or highly specific projects. But the greatest community benefit often comes from unrestricted support for core operations of nonprofits doing preventative work. Focus on the outcomes you want to see (kids graduating, people housed, etc.), and fund or volunteer accordingly.

Engage Your Workplace or Peers: If you’re in a position of influence at your workplace, advocate for more robust giving and volunteering programs. Many companies will match employee donations–if yours doesn’t, ask leadership to consider it. Leaders can set the tone by tying corporate giving to company values and by celebrating employees who give back. Even if you’re not the CEO, you can rally colleagues in a giving circle or a fundraiser for a cause you all care about. Collective action multiplies impact and also sends a message to public officials that the community is invested in these issues.

Plan for Public Underinvestment: It’s a sad reality, but public budgets are likely to remain uncertain. Rather than throwing up our hands, we should prepare to be part of the solution. This could mean committing to a recurring monthly donation to a nonprofit you love, or making a multi-year pledge to sustain a program even if government funding falters. It could also mean volunteering to support fundraising efforts, or contacting representatives to support funding for education, housing, and healthcare.

When we fund nonprofits as investments in our collective future, we create a different cascade entirely. Collapse is not inevitable. We are not powerless. We can choose differently. Margins are only margins until enough of us step forward and redraw the lines.

Instead of students dropping out, they graduate. Instead of families in crisis, there’s safety in our homes. Instead of burying our head in our hands, we build stronger communities, we support the supporters—this is how we stick together, this is the glue.

Thank you for this Kelly. Your words helped me get my head around the crisis I knew we were in but didn’t understand the scope or scale of. I feel like I have something I can share to explain the problem now. And thank for ending things on an actionable note, it’s hard to see ways forward through all that is happening. This shines a light on a path to travel through the current darkness.

Thank you, Kelly—another great read! This topic is especially close to my heart. I’ve spent over a decade in the nonprofit space, serving as an advisor, consultant, leader, volunteer, and board member. Unfortunately, this issue is not new to the nonprofit world and highlights many of the sector’s systemic challenges.

One of the most persistent hurdles I face when consulting for nonprofits is helping them understand that “nonprofit” is a tax designation—not a business model. In my experience, many nonprofits are founded by passionate individuals with deep connections to specific issues, but often without a business background. Successful nonprofit leaders typically approach the organization like a business, applying fundamental principles of sustainability and strategy. Here are a few core examples:

Market Saturation: The nonprofit space is severely overcrowded. Creating a nonprofit has a low barrier to entry, which has led to an overabundance of organizations. I’ve been asked to help start new nonprofits more than a dozen times, and I’ve declined every invitation. While I’m genuinely honored to be asked, I always explain that my decision stems from a belief that there are already too many nonprofits in that given cause area. I encourage people to channel their energy and passion into existing organizations. If none align with their specific vision, they can still contribute by helping an existing nonprofit diversify or evolve its approach.

Economies of Scale: Managing nonprofit funding is challenging—not just because it’s limited, but because overhead costs are real and substantial. When you create a new nonprofit, a portion of every dollar raised must go toward infrastructure—accountants, rent, legal fees, IT, and more. If, for example, there’s $100 available for nonprofits in a community and it's split among five organizations, the impact of that $100 is diminished. Five different overhead structures mean diminished overall efficiency. Consolidating efforts and resources would allow fewer nonprofits to stretch funding further and achieve greater impact.

Diversification: As we saw with CSF, nonprofits often lack diversified funding streams. Many rely disproportionately on one source, simply because they lack the staff or resources to pursue alternatives. This ties back to the burdens of overhead and capacity.

Financial Impact & Restraint: Occasionally, I see calls on social media encouraging people to give to small nonprofits instead of large ones because "a larger percentage of funds goes directly to the cause." While well-meaning, this argument overlooks the efficiency and reach of larger nonprofits. Moreover, many grants restrict funding to specific programmatic outcomes, which means nonprofits often struggle to cover essential operational expenses. It’s not unusual to find organizations that are technically cash-positive yet unable to pay salaries or rent because those funds are restricted. (Before the pandemic, a few of the country’s largest philanthropies recognized this issue and agreed to shift their funding models to allow more of their grants to support general operating costs.) Too often, nonprofits overextend themselves and are unprepared for lean periods.

I could go on about the structural challenges of the nonprofit model, but I also want to highlight something more insidious at play. Ending federal funding so suddenly and dramatically is a deliberate political strategy—one designed to push blue states toward purple. Blue states typically offer more state and local funding to their residents, but when federal funding disappears, those governments are forced to make impossible decisions. CSF is a direct example of this. It’s easy to blame Washington state for the program’s collapse, but we must consider the broader strategy—and recognize the deeper, more dangerous motives at play.